Minimizing the size of Docker images using multi-stage builds

Update (Mar 6 2022): there are now different official OpenFOAM images available, which are tailored to development or application. The images are also build in multiple stages and have increasing features/size with each stage.

- A multi-stage build version of hello world

- Single-stage build of dummyFoam

- Analyzing library dependencies

- Multi-stage build of dummyFoam

- Summary

When compiling a new high-level application or utility that will be shipped as a container, ideally, you want to start from a base image that comes as close as possible to the build-environment you need to compile your application. For example, if you’re going to create and build a custom OpenFOAM® solver, it makes perfect sense to start with the OpenFOAM Docker image as a base. You may install additional third-party libraries, copy your sources to the image, and compile. This workflow is really convenient since it allows, for example, to compile your application against a variety of OpenFOAM versions or flavors at lighting speed while keeping all dependencies nicely separated. One disadvantage, however, is the quickly increasing storage demand since every newly created image contains both the build-environment and the application. Moreover, sending the image over the network will take longer and cause significantly more traffic. Of course, there is an established way to overcome these disadvantages called multi-stage builds, and this article tells you how to apply it to OpenFOAM applications.

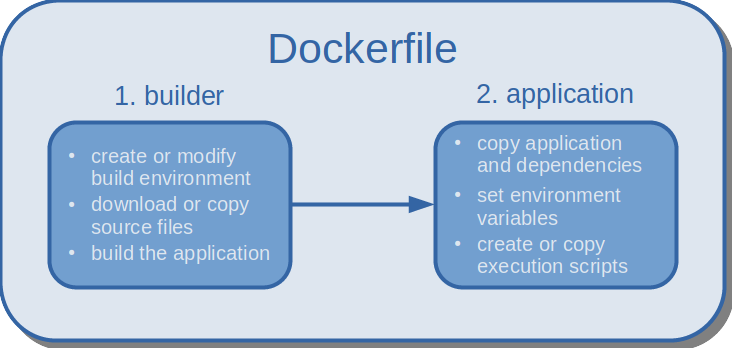

The idea behind multi-stage builds is simple: first, you prepare one or more build-environments with all dependencies (typically called builder(s)), then you build your application, and finally, you extract only what is really needed from the builder and discard the rest. The simplest multi-stage build is a two-stage build as depicted in the image below. However, you could also merge applications from multiple different builders into one final image, or you could combine different builders to create a new builder. The first scenario may be relevant to merge several binaries needed to run a simulation into a single image (e. g. third-party meshing tool + custom OpenFOAM solver + third-party post-processing tool). The latter scenario may occur if OpenFOAM is combined with another custom library to build the final app. In the early days of Docker, users would define individual Dockerfiles for each step in the build process, and write wrapper scripts to execute them in order. Since the introduction of multi-stage builds, Docker handles the execution and copy processes for the user, and the entire build can be defined in a single Dockerfile.

|

|---|

| Multi-stage build with two stages: in the first stage, the environment is set up and the application is compiled; in the second stage, the compiled application and its dependencies are isolated. |

A multi-stage build version of hello world

Let’s start with the probably simplest app we can build in a multi-stage process as outlined before: hello_world.cpp. If you want to follow along:

mkdir hello_worldcd hello_worldtouch hello_world.cpp- copy & paste the source code from the box below into

hello_world.cpp

#include <iostream>

using std::cout;

int main(){

cout << "Hello World - multi-stage edition\n";

return 0;

}

To build the app, we start with the official Ubuntu 18.04 Docker image, update the list of available software packages, and install a C++ compiler. Note that the ~120MB Docker image of Ubuntu is not comparable to the richly packaged desktop version you may use on your workstation, so you’ll probably have to install more dependencies than you’re used to. The actual compile command to build the program follows in line 5. Compiling the app concludes the first stage.

In the second stage, we start with an empty Docker image (basically FROM scratch) and copy only the binary called hello from the first stage over to the final image. The possibility to name different stages makes it easy to write comprehensible Dockerfiles. In the example below, our base image is simply called builder. This name is then used in the second stage to run the COPY command. By default, the hello program is executed whenever we run a container.

# first stage

FROM ubuntu:18.04 AS builder

RUN apt-get update && apt-get install -y g++

COPY hello_world.cpp /

RUN g++ -static -o hello hello_world.cpp

# second stage

FROM scratch

COPY --from=builder hello /

CMD ["/hello"]

To build and run the hello world multi-stage version,

- create a new Dockerfile

touch Dockerfile, - copy & paste the content of the code box above into the Dockerfile, and

- execute the Docker commands provided in the code box below.

docker build -t hello_world:multi_stage .

docker run hello_world:multi_stage

# output ...

Hello World - multi-stage edition

I hope you’ll agree at this point that Docker multi-stage builds enable us to create streamlined build processes. The same overall two-step structure can be applied to build OpenFOAM apps, too. However, there are some technicalities that require a couple of intermediate steps to create a runnable and isolated binary. Therefore, we’ll first take a look at how dummyFoam is built in a single-stage process.

Single-stage build of dummyFoam

dummyFoam consists only of the basic app structure that the foamNewApp utility creates. The app does nothing more than setting up a root-case and creating a (run)time object. In case you want to follow along, I have set up two Github repositories to make your life easier:

git clone https://github.com/AndreWeiner/of_app_isolation.git

cd of_app_isolation

git clone https://github.com/AndreWeiner/dummyFoam.git

With the commands above, we have downloaded one repository into another. The commands issued later on require precisely this folder structure. The first repository contains the Dockerfiles for single and multi-stage builds. The second one comprises a version-controlled form of dummyFoam. Let’s now have a look at the single-stage build.

FROM openfoamplus/of_v1912_centos73

# copy app source code to base image

COPY dummyFoam /opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/applications/solvers/dummyFoam

# change working directory

WORKDIR /opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/applications/solvers/dummyFoam

# source environment variables, compile, and create execution script

RUN source /opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/etc/bashrc && \

wmake && \

mkdir /case && \

echo "source /opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/etc/bashrc &> /dev/null; dummyFoam -case /case" > /runDummyFoam.sh

We start with version 1912 of the OpenFOAM-plus release as a base image. The image comes with all dependencies needed to build dummyFoam. Next, we copy the app sources to the image and make the app folder our work-directory. The RUN command sources the OpenFOAM environment variables, builds the app using wmake, and creates a new folder in the root directory. The case folder serves as a mount point to attach simulation cases.

Commands to build the dummyFoam image and to create a container are provided in the code box below. We use the latest commit on the master branch of the dummyFoam repository (the default state after cloning the repository). One could also checkout another branch before copying the sources and building the image. To track the branch/commit used, it is good practice to tag the image with the commit hash (or at least a unique portion of it).

# build the image

docker build -t andreweiner/dummy_foam:$(git --git-dir dummyFoam/.git log -1 --format=%h) -f Dockerfile.single .

# create a container

docker container run -it andreweiner/dummy_foam_single:06ff344 /bin/bash

# now we are inside the container

# let's see where the dummyFoam binary file is located

which dummyFoam

# output ...

/root/OpenFOAM/-v1912/platforms/linux64GccDPInt32Opt/bin/dummyFoam

With the latter two commands in the code box above, we can see where in the image the dummyFoam binary is located. However, this time it is not as easy as copying the binary over to the second stage. A little twist I didn’t comment on earlier in the hello_world.cpp example is the flag -static. Even though the hello world program is relatively simple, it already has quite some dependencies on other libraries. An obvious example is iostream from the C++ standard library. But the standard library links against other C libraries which will be therefore also needed in the hello program. If one of these dependencies is missing in the second stage, the linker (a tool provided by the operating system to handle library dependencies) will complain and crash as soon as we try to execute the binary. So why did it work in the first example? The answer is that the flag -static tells the compiler to create a static version of the program. A static program is one that does not dynamically load any other libraries at runtime. In other words, the compiler packages all the dependencies into a single executable binary file. The reason why not every program is compiled statically is the subsequent massive redundancy of binary code. Each and every C++ program, for example, would very likely contain the entire C++ standard library.

Coming back to the compilation of dummyFoam, unfortunately, it is not as easy as adding a flag to the wmake options. We would have to tinker around with the base image, and presumably create a new one. Here, we follow another path. In theory, we just have to find all the libraries dummyFoam loads at runtime and copy them over to the second stage together with the dummyFoam binary itself. This workflow may sound cumbersome, but, luckily, it can be automated to a large extent as you’ll see in the next section.

Analyzing library dependencies

ldd is a tool that invokes the (dynamic) linker and allows us to trace dynamic library dependencies. The output of ldd is formatted as shared_library.so => /path/to/shared_library.so (address in memory) (learn more). dummyFoam loads several OpenFOAM-specific and some system libraries, as can be seen in the code box below. Note that you have to be inside the container created after the single-stage build to invoke to command in line 1 of the code box.

ldd $(which dummyFoam)

# output ...

linux-vdso.so.1 => (0x00007fff811f7000)

libfiniteVolume.so => /opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/platforms/linux64GccDPInt32Opt/lib/libfiniteVolume.so (0x00007f1220154000)

libmeshTools.so => /opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/platforms/linux64GccDPInt32Opt/lib/libmeshTools.so (0x00007f121f930000)

libOpenFOAM.so => /opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/platforms/linux64GccDPInt32Opt/lib/libOpenFOAM.so (0x00007f121ecc1000)

libdl.so.2 => /lib64/libdl.so.2 (0x00007f121eabd000)

libstdc++.so.6 => /lib64/libstdc++.so.6 (0x00007f121e7b4000)

...

What we actually need from the ldd-output are the paths to all shared object libraries (*.so files). To extract the path from each line, we pipe the output to cut, split the line at every whitespace, and keep only the third element/field. The output of cut can be piped again to xargs, which converts the line-wise output of cut into a single line containing all paths (basically, an argument list that can be used by yet another program).

ldd $(which dummyFoam) | cut -d" " -f3

# output ...

/opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/platforms/linux64GccDPInt32Opt/lib/libfiniteVolume.so

/opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/platforms/linux64GccDPInt32Opt/lib/libmeshTools.so

/opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/platforms/linux64GccDPInt32Opt/lib/libOpenFOAM.so

/lib64/libdl.so.2

/lib64/libstdc++.so.6

...

ldd $(which dummyFoam) | cut -d" " -f3 | xargs

# output ...

/opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/platforms/linux64GccDPInt32Opt/lib/libfiniteVolume.so /opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/platforms/linux64GccDPInt32Opt/lib/libmeshTools.so /opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/platforms/linux64GccDPInt32Opt/lib/libOpenFOAM.so /lib64/libdl.so.2 /lib64/libstdc++.so.6 ...

Did this single-line command seem too easy to work? It sometimes is because there is another stumbling block you may encounter. Many operating systems, like Ubuntu, allow having multiple versions of the same library. To manage these dependencies internally, there is usually a symbolic link pointing to the default version of the library. One example in the case of dummyFoam is the C++ standard library. If we inspect the path returned by ldd using ls -al, we find that /lib64/libstdc++.so.6 is actually pointing to the specific version libstdc++.so.6.0.19 in the same directory. The tracing of ldd does not follow symbolic links, so we have to keep that in mind when copying the library files. You’ll read in the next section to overcome this issue.

ls -al /lib64/libstdc++.so.6

# output ...

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 19 Jun 5 2017 /lib64/libstdc++.so.6 -> libstdc++.so.6.0.19

Multi-stage build of dummyFoam

Finally, we are ready for the multi-stage build of dummyFoam! In the builder stage, we package the libraries required by dummyFoam into a tar-archive. In the tar command, it is essential to add the --dereference flag. This option tells tar to follow symbolic links and to archive the actual file and not the link pointing to it. In the last step of the first stage, another file not captured by the cut command is added to the archive, and a second archive containing OpenFOAM configuration files is created.

# step 1: build application using base image with build environment

FROM openfoamplus/of_v1912_centos73 AS builder

COPY dummyFoam /opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/applications/solvers/dummyFoam

WORKDIR /opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/applications/solvers/dummyFoam

RUN source /opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/etc/bashrc && \

wmake && \

ldd $(which dummyFoam) | cut -d" " -f3 | xargs tar --dereference -cf libs.tar && \

tar --dereference -rvf libs.tar /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 && \

tar -cf etc.tar /opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/etc

The base image for the second stage is Alpine, a minimalistic operating system specifically designed for Docker images. Alpine has a package manager and enables us to install basic command-line tools like bash and tar. Next, we copy the dummyFoam binary, the required dynamic libraries, and the configuration files from the builder and extract the archives. Note that the absolute paths of all files will be the same in the second stage. The remainder of the Dockerfile configures environment variables and creates an execution script that runs dummyFoam in the /case folder (similar to the single-stage build).

# step 2: isolate application and dependencies

FROM alpine:latest

RUN apk add --no-cache bash tar

COPY --from=builder /opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/applications/solvers/dummyFoam/libs.tar \

/root/OpenFOAM/-v1912/platforms/linux64GccDPInt32Opt/bin/dummyFoam \

/opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/applications/solvers/dummyFoam/etc.tar \

/

RUN tar -xf libs.tar && \

tar -xf etc.tar && \

rm *.tar && \

sed -i '/projectDir=\"\$HOME\/OpenFOAM\/OpenFOAM-\$WM_PROJECT_VERSION\"/c\projectDir=\"\/opt\/OpenFOAM\/OpenFOAM-\$WM_PROJECT_VERSION\"' /opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/etc/bashrc && \

mkdir case && \

echo "source /opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/etc/bashrc &> /dev/null; /dummyFoam -case /case" > runDummyFoam.sh

ENV LD_LIBRARY_PATH=\

lib:\

lib64:\

/opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/platforms/linux64GccDPInt32Opt/lib:\

/opt/OpenFOAM/ThirdParty-v1912/platforms/linux64Gcc/openmpi-1.10.4/lib64/lib:\

/opt/OpenFOAM/OpenFOAM-v1912/platforms/linux64GccDPInt32Opt/lib/openmpi-1.10.4:\

/opt/OpenFOAM/ThirdParty-v1912/platforms/linux64Gcc/openmpi-1.10.4/lib64

To perform the multi-stage build, run docker build -t andreweiner/dummy_foam:$(git --git-dir dummyFoam/.git log -1 --format=%h). If the image build succeeds, you should be presented with a teeny-tiny but executable version of the custom solver. You can test the image as follows:

- on the host,

cdinto any valid OpenFOAM test case; if you have a local installation, you may runcd $FOAM_TUTORIALS/basic/laplacianFoam/flange/ - run

dummyFoamin the test case usingdocker container run -it -v"$PWD:/case" andreweiner/dummy_foam:06ff344 /bin/bash /runDummyFoam.sh > log.dummyFoam

The solver output in the log-file should look as follows:

...

Create time

ExecutionTime = 0 s ClockTime = 0 s

End

Summary

To conclude this somewhat lengthy post, let’s see how much space we actually gained thanks to the multi-stage build. To get the precise image size in bytes, run docker image inspect IMAGE_ID --format=''. When sending an image over the network, e. g. to Dockerhub, the image is typically compressed using gzip. So, the important numbers are the size of the image on our system and the size of the compressed archive. To save the single and multi-stage build outcomes as compressed archives, check out the code box below.

## OpenFOAM base image

docker save openfoamplus/of_v1912_centos73:latest | gzip > of_base.tar.gz

du -h of_base.tar.gz

# output ...

653M of_base.tar.gz

## isolated dummyFoam app

docker save andreweiner/dummy_foam:06ff344 | gzip > dummy_foam.tar.gz

du -h dummy_foam.tar.gz

# output ...

42M dummy_foam.tar.gz

The table below displays the final numbers. The difference between the base image and the result of the single-stage build is less than 1 MB. The multi-stage build yields an image that is about 15 times smaller than the one resulting in the single-stage build. Another interesting idea is that adding more apps to the multi-stage build would presumably lead to a marginal increase of the final image size since other apps access mostly the same shared objects libraries as dummyFoam does.

| version | image size | compressed |

|---|---|---|

| OpenFOAM-v1912 | 2481 MB | 653 MB |

| dummyFoam + OpenFOAM-v1912 | 2481 MB | 653 MB |

| dummyFoam | 160 MB | 42 MB |

I hope you found some useful code snippets or ideas while reading the post.

Cheers, Andre